This summer I lived in a Buddhist monastery for three months. When I tell this to most people their first reaction is that I’ve sentenced myself to some sort of prison. It’s not usually something they say out loud, but it shows up in their facial expression, body language and tone of voice. Our society clearly views a monastery as a place that is opposed to life in the “real” world, and this makes it rather scary for many.

Ironically, such a reaction arises not only from ideas of monastic life that are largely uninformed, but how people view their own lives is rarely an accurate portrayal of what is really going on. When seen from the monastic viewpoint, “real world” life is actually the prison to be escaped. The creation of monasteries was intended to provide a cocoon in which seekers of truth could live a pure life and explore their inner world without distractions.

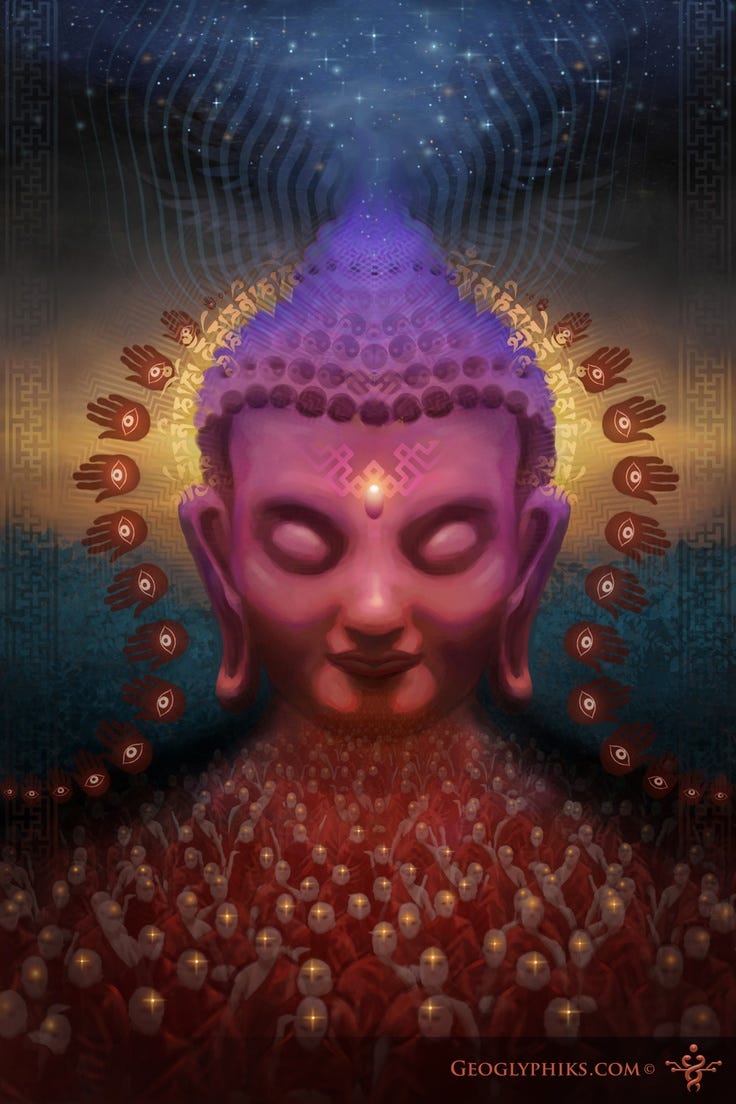

So, what is the truth? I cannot lay claim to a universal truth that works for everyone, but I can share my own experience…perhaps it will enrich and expand you. Ultimately, the goal is to carry the Buddhas teachings and state of consciousness wherever you are — urban center or monastic retreat.

The Daily Flow

Skycliffe is a Buddhist monastery nestled in the kettle river valley in the interior of British Columbia. This 220 acre property is largely wild terrain, with about 40 acres being actively used and maintained by the resident monks on the property. The Buddhist Teacher, Wisdom Master Maticintin, is by no means a conventional one. She founded HUMUH: Transcendental Buddhism as a fourth Buddhist school, culling the nectar of essential teachings from the various Buddhist vehicles into a clear and direct Buddhist Path that is both pragmatic and capable of guiding disciples into some of the deepest aspects of human consciousness.

Every morning we arise around 5:30 am, meeting in the forest temple at 6:30 to read a meaningful prayer, chant a 66 stanza mantra, and then meditate for little over an hour. Work begins at 9 am and the whole operation runs like a pretty tight ship. Mostly the men are working outdoors on the property on a wide range of activities: tending gardens, mowing lawns, chopping wood, repairing things, building structures, painting etc. Many of the women are working in the main house editing videos and books, transcribing, developing communications to the sangha — while both women and men are actively involved in the lunch preparations.

There is a spiritual teaching or practice from 11am to noon, and lunch is usually around 1 pm. People then continue to work until 5 pm after which we break until we meet again at the forest temple for another hour of meditation at 7pm. After evening meditation some people return to the dining hall for tea, study or to briefly check the internet (there is no cellphone reception on the property), and then head back to their quarters for the night.

Work is viewed as a spiritual practice where everyone works as a collective – practicing mindfulness while supporting with tasks and maintaining good communication. There is very little ego involved and everyone is in the spirit of service. Many of the monks are older and have secured funds; being able to live on the property without relying on donations creates refreshing degree of independence and allows everyone to focus on the most important work at the Buddhist monastery — spiritual awakening. I was on a work-study that provided me accommodation and participation in the Teachings in exchange for labor, and I contributed a modest sum to cover food expenses (we are very well-fed with nutritious and delicious food to sustain us).

Its all about intention

The Buddha created the monk order and the monastic life as a way of fast-tracking individuals who were keen to attain to the spiritual realization of Buddhahood in their lifetime. He was a pragmatic man with a keen insight to human nature — he knew our propensity for distraction, our tendency for unconscious habitual behaviour and the difficulty of changing ourselves without support systems. Just as someone who wants to recover from a serious illness will go to a hospital to heal, or a music student to a conservatory to study, a monastery is a place to heal inner divisions, study pure wisdom teachings and restore clarity to the delusive mind.

Because urban life encourages a frenetic pace of living — laden with distractions of all kinds — a monastic life is often more suited for focused spiritual development. Work is performed in the context of natural life with a collective of individuals that share a unified intent. While not highly social, there is an invisible yet tangible bond between monastics and community members who share a deeply held mission to heal and awaken for the benefit of all.

While living a monastic life for an extended period of time helps us to become more natural in many ways, the challenge is to integrate this state of being with our worldly life when we return. We can develop a rigidness in outlook or an “allergy” to many socially accepted conventions depending on the rules of the Buddhist monastery and the style of teaching, but sometimes that is just part of the territory so it’s up to each individual to figure out how to “live in the world but not of it”.

The Way of the Disciple at Buddhist Monastery

The most valuable thing I learned at the Buddhist monastery was how to be a disciple. The root of the word “discipline” is “disciple”, and while the word has fallen out of favor in modern times, a wholesome discipline can foster human dignity, integrity, and nobility. Living a disciplined life rooted in a noble aspiration for spiritual evolution encourages an innate sense of self-confidence that isn’t derived from the ego.

While it is possible for the ego to lay claim to this discipline and its aspirations — what spiritual teacher Chogyam Trungpa referred to as “spiritual materialism” — the presence of the Teacher is a balancing force. As we apply ourselves day-in and day-out to the steady work of training our minds, we become more aware of our habits and delusive thoughts, as well as the inherent joy and clarity that is our natural state. We discover something very beautiful and wholesome about ourselves, something that does not need to be defended nor promoted by ourselves our society…in essence, we start to discover our authenticity as Divine beings.

When people ask me why I go to study at the monastery, I tell them that I love it. To wake up each morning to the sound of the river running by, to hear the temple bell calling me to sit in the silence, to experience the flashes of insight and deepening peace of nature, to listen to pure Teachings that resonate the truth, to return to bed each night knowing that in some small way I may have moved closer to authentic freedom — is a precious gift.

While I don’t envision myself living as a full-time monastic, the Buddhist monastery life is a form of cleansing, disciplining and immunizing the body, mind and spirit to live in the “real world”. I believe it’s an essential opportunity for a sincere spiritual aspirant who wants to learn to live a meditative life and discover a greater sense of naturalness. It is important to find a monastic path that is not steeped in ritual and dogma (unless that is what you want); I am lucky to have found such a path and a Teacher — so I can say that they exist.

Changes for the better at Buddhist Monastery

Over time many of the attachments to people, things, and situations that no longer serve you will be seen for what they are and naturally fall away. People fear change, and the truth is that giving yourself wholeheartedly to living a monastic life for any reasonable amount of time will change you — I can attest.

There is the danger of developing an aloofness and a colder kind of detachment, but this is an aberration of the Buddha’s true teachings. Our detachment is intended to give us the freedom to love without strings attached, to give without expectation and to relate without clinging. It is a different way of living life than we are taught from family and society; as with any deep change, there are growing pains along the way.

It’s important to remember that there’s nothing to lose that wasn’t truly yours to begin with — most of what we identify with as ‘ours’ is just an attachment to an idea. Many years ago a peruvian shaman told me “everything is for you, but nothing belongs to you.” What we practice in the monastery is this form of responsibility— to become responsible for our inner and outer world, to be discerning in our choices and conscious of what we bring into our world knowing that what we feed is what will grow. Perhaps this is the deeper meaning of religion.

Living at the Buddhist monastery returned me to a noble simplicity, helping me clear space to focus on what I truly want and disciplining me to see that all conditions are contained in the mind. One day you may choose to give yourself the gift of putting the world aside for a time, not as a vacation, but for the purpose of discovering a different way of life and performing a more integrated kind of work that brings our inner and outer worlds closer together. It is an essential education that is missing from our culture, so consider taking a break off that kit-kat bar that we call the “real world” and take a chance to taste something totally different for a time…it just might change you for the better.

Never want to miss an article? Follow Zamir Here on Medium

See Also: A Vision of Yoga for our Time

This summer I lived in a Buddhist monastery for three months. When I tell this to most people their first reaction is that I’ve sentenced myself to some sort of prison. It’s not usually something they say out loud, but it shows up in their facial expression, body language and tone of voice. Our society […]

3 months in a Buddhist Monastery